Racing Rebirth—Jack Roush revitalized his legendary Mustang II Pro Stock racer with a fresh engine from Roush Competition Engines

Written by Phillip Thomas

Photography by the author and courtesy of ROUSH

Under a humid spring morning in March of 1974, Wayne Gapp and Jack Roush relaunched their fresh Mustang II Pro Stock machine for a weekend of match races during Gatornationals. The Mustang II only debuted six months prior, and the duo was quick to pick one up on the rumor that it was slipperier in the wind than even the venerable Pintos. Roush would pilot the new Mustang II, while Gapp drove his Pinto.

The Mustang II had come together at the Livonia compound in Michigan, where the winter weather had prevented them from getting any real full-tilt testing done. What few eighth-mile test hits they gathered at Milan were usually met with the new car “dancing” all over the cold, wintery track conditions up north, in Roush’s words.

But with the Sunshine State’s pavement radiating with warmth, Roush worked the Mustang II like anything else. He went through the burnout box, found his spot in the timing beams, sidestepped the clutch, and came off the line in the usual routine… before the cabin was rapidly and unexpectedly exposed to the outside world at more than 150 mph like a beer can peeling apart while being shot out of a cannon.

“The first qualifying run at Gainesville, I got it up to speed and the decklid was not properly attached to the roof and I set an altitude record on decklids,” Roush proclaimed. “In the traps, all of a sudden, I hear all this noise, and the cockpit fills with combustion gas. I look around and all I can see is the whole back-end is off the car. So, it destroyed the decklid—and the Mustang II is a brand-new car in 1974. I sent somebody to Jacksonville to get a white Mustang II rental car. I took the decklid off the Hertz rental car and ran its decklid on my car for the rest of the race.”

Still, a 9.02 elapsed time on the first full hit put any questions to rest about the potency of this new combo, with that first weekend in the Mustang II at Gainseville settling with Low ET of the Meet with an 8.88 before finding itself in the finals against Wally Booth (who ran 8.87), falling to his Hornet despite the strong debut.

The Gapp and Roush Mustang II never quite held the acclaim of some of Roush’s other machines, but it’s one of the only original examples to have survived the decades. It existed in tragic irony, with the NHRA blaming the shorter wheelbase of Ford’s potent Pintos for their advantage and instituting new weight breaks that effectively made the 96-inch Mustang II useless for the class before it even made its first pass (the longer Tijuana Taxi was under construction at the same time due to the rules changes).

Despite this, it remained in the back of his mind as something of a missed opportunity. Roush himself has finally settled down a little, partly after a bout with cancer and partly due to the pandemic itself idling motorsports, and he’s had time to reprioritize his efforts at home. The Mustang II left stashed in a dark corner of the shop for close to 30 years, became the target of Roush’s notoriously intense, laser-beam focus.

Like Dyno Don’s Mustang II, Don Hardy was phoned up to build the double-rail tube chassis. Little tricks here and there are simply a result of the times, despite being something of a silhouette car, you still find a smattering of factory parts throughout — notably, the upper and lower control arms, modified Corvair and Chevy II arms, specifically. Trimmed down for packaging around the chassis and headers and tied to a set of aluminum Strange Engineering uprights, the arms are supported by Monroe coilovers. A Pinto steering rack was used, and in a you’ll-never-see-this-today example of old-school problem solving, a flexible spring shaft/coupler was used to link the column to the rack-and-pinion. Not unlike those flexible spring socket extensions, but certainly unlike any solution you’ll find today. Following those frame rails towards the back, the narrowed 9-inch housing was hung by a pair of ladder bars. Schiefer 5.67 gears were wrapped around a Strange Engineering spool, with Strange axles branching from there to the Motor Wheel rear hoops shod with 14x32x15 Firestone slicks.

Unlike Dyno Don’s Mustang II, Gapp and Roush only chose to acid dip the doors, rationalizing the choice in that the weight loss would be replaced in Bondo just to get the panels straight again, and ideally, the body would last longer over time. Though they were part of the Ford factory team, they still operated their cars like an OEM program. The Mustang II lived up to those expectations wherever it could. The front sheet metal was replaced with fiberglass panels from A&A as standard practice, and throughout the chassis, new ballast mounting locations were added so that Gapp and Roush could get a real handle on weight transfer. To seal everything in, Chuck Miller painted a disco-era perfect strip package that was dominated by the Blue Oval’s official colors suspended deep under metallic flake before Paul Hatton lettered the Mustang II up.

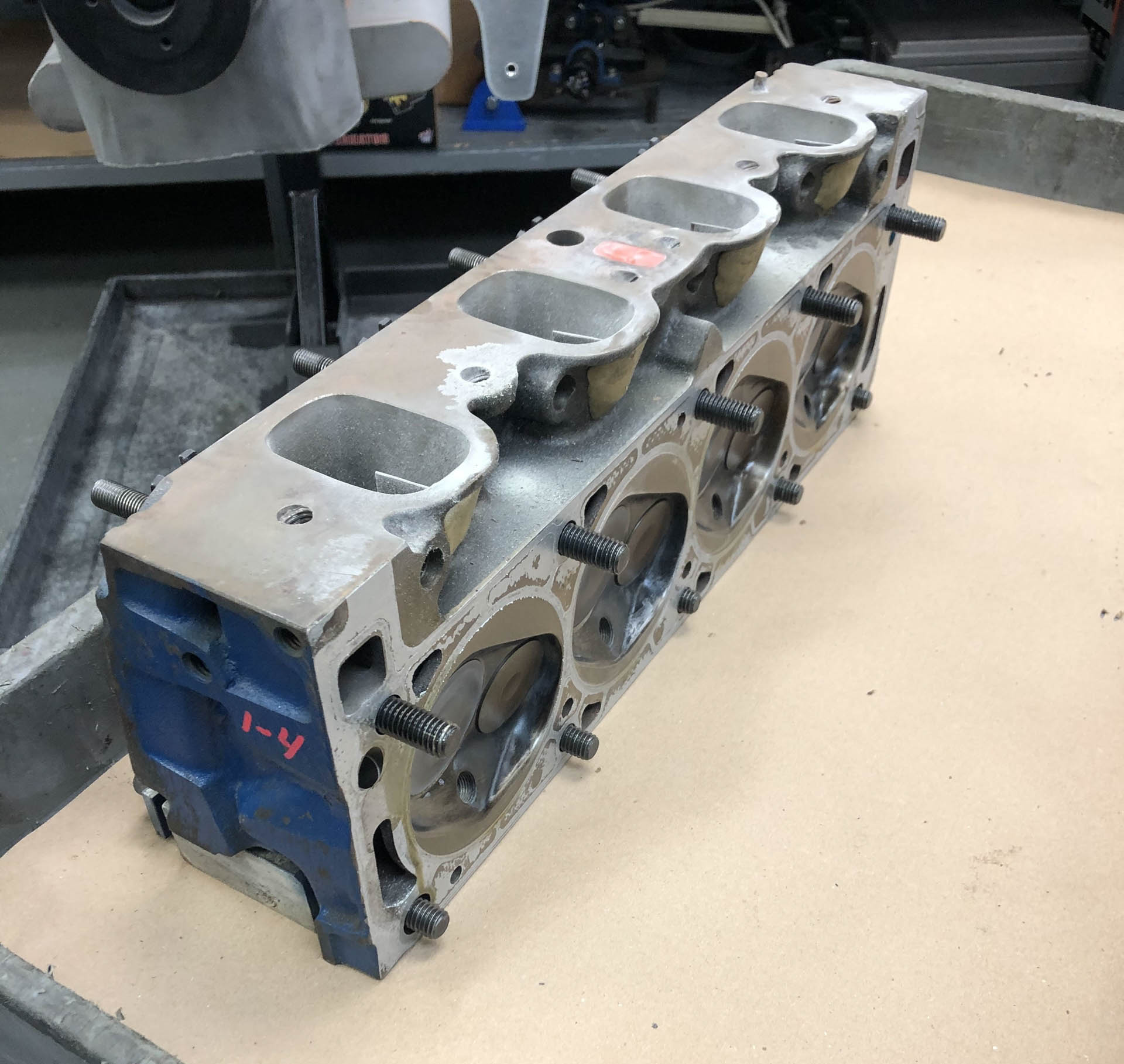

All this was wrapped around a factory-block 351 Cleveland that kept the stock bore and stroke, but beyond that, little remained faithful to the Blue Oval’s original specs. Roush machined custom Chevy rods to fit the 351 crankshaft by BRC (increasing rod length from 5.775 inches to 6.060 inches, moving the piston wrist-pin location to accommodate), who also produced the one-off, Gapp-and-Roush-designed, set of pop-up pistons. In an era before dry sump became routine, Gapp and Roush’s team would relocate the oil pickup in the heavily-modified and baffled oil pan, running a section of hose to a fixed oil pump pickup intake down in the sump to eliminate the failure-prone factory pickup tubes. They also transformed the oil pan with a rear-sump configuration to allow the steering hardware room to swing. Trap doors, along with a widened reservoir that flared out from the sides, worked together to retain a supply of oil down low, keeping the oil galleys above fed as much as keeping windage down. Gapp and Roush utilized oil restrictors designed for Moroso to force as much volume as possible into the main bearings.

As you work your way up the combo, there’s still a wealth of tricks to off-the-shelf hardware. Notably, the heads had high-port adapter plates designed for the exhaust ports to improve their overall trajectory out of the combustion chamber. Every facet of the ports and chambers was also tweaked before a heavily chopped Edelbrock tunnel ram was set atop. It had its plenum volume reduced and excess webbing was removed to improve airflow around the runners, which were also shortened to optimize the nipped-and-tucked tunnel ram for the buzzing rpm range of Pro Stock.

The whole song-and-dance was led by a General Kinetics camshaft, which bumped a set of GK roller lifters before flipping that motion over the now obsessively tweaked top-end. The stock guide plates were modified such that each could be fitted to an individual pushrod’s geometry. GK roller rockers ride underneath a Jomar stud girdle before a set of factory rocker covers — cut and welded over another pair to double-up the height — capped all those metallic secrets.

Handling the fueling are a pair of 1050 CFM Holley Dominators, though the ignition system was a trick example of early electronic ignition, utilizing ACCEL’s BEI system which placed an optical ring on the distributor shaft, with a phototransistor that found timing via a series of gaps in the BEI’s disc — not unlike GM’s Optispark. This gave them timing control down to the quarter-of-a-degree. Naturally, towering Lenco Levers split gears behind the 351, with a Long-style lever clutch taking up the task of capturing all the rotating chaos possible from 10,000-rpm launches.

And Back to Today

As Tyler Wolfe, Roush’s Historian, and I rounded the corner of the shop, there he was. Roush and one of his restoration guys were making a handful of adjustments to the linkages while the Lenco was on a bench after its initial post-restoration test. Frankly, it also just seemed like he was reliving a highlight reel he hadn’t had in the memory banks for some time — working his routine across the levers subconsciously before carefully resetting them one by one, racking each forward like a bolt-action.

This same building used to host many NASCAR Cup-car builds, a side room where Merlin V-12s are hoarded was once the engine dyno lab. While Covid had him home in Livonia more and more, and further away from the grind of chasing his Roush-Fenway-Keselowski Racing cars across the country, Roush finally decided to reclaim the space and began working on not just his projects, but restoring examples of his children’s and grandchildren’s race cars. However, it was also the purgatory for the Mustang II for many decades, practically forgotten about while Roush built his empire.

“I thought I was gonna live forever and that I could do it whenever I wanted. A couple of things happened to my health that gave me wakeup calls, so I said, ‘If I'm going to get this thing together and put it back in the same condition it had in its heyday, I need to do it now, not leave it to someone else to do later,’” Roush explained. “I had some cancer, and I had some challenges with that. I made a short list of what I wanted to do with my time and fixing that car was one of them. I don't have any more Pro Stock cars, but when my daughter Susan [Roush-McClenaghan] decided to start drag racing 10 years ago, I had a crew of two or three people who worked on restorations for me all the time. I had the engineering business doing well, and I had the road racing business and NASCAR business doing well. And so, since I worked seven days a week for the company, I wanted to do something for myself. That's when I started restoring all these Pro Stock cars. I let the company pay since I was being productive!”

After that initial outing in 1974, Roush would continue to campaign the Mustang II for the rest of the season in match races, but with the NHRA’s wheelbase rules still pulling the strings, it had lost its chance as a full-time contender in Pro Stock. The following year, 1975, Gapp and Roush dissolved their union due to irreconcilable differences in business. Jack sold the Mustang II to Luis Forteza, who imported the de-branded Pro Stocker to Puerto Rico, where he campaigned it over several years with his family. In the time since, Roush moved away from Pro Stock, entering NASCAR, Trans-Am, and international endurance racing over the following decades.

The empire sprouted, first with Roush Performance Engineering, branching off into Engine & Control Systems (which grew into Roush Industries for their non-motorsport clients), later Roush Performance Products for the DIY crowd building their hi-po Mustangs — today, a stroll down the block reveals what feels like a dozen or more buildings around Livonia where a different tangent of business is housed. Even when the opportunity arose in the ’90s to repurchase the Mustang II, it was, of course, put out of sight, far out of mind while these off-shoots grew.

With decades of neglect, the car was rough, but still fairly complete. The work was spearheaded by Andy Robinson and Steve Fackender. Every composite part in the nose had warped with age and use but was still repairable. The body came to them with less paint, but it too was in great shape, all things considered. Most of the time was just spent fixing fitment issues. In the process, every decal was scanned, cataloged, and recreated — building something of a small archive in the process too.

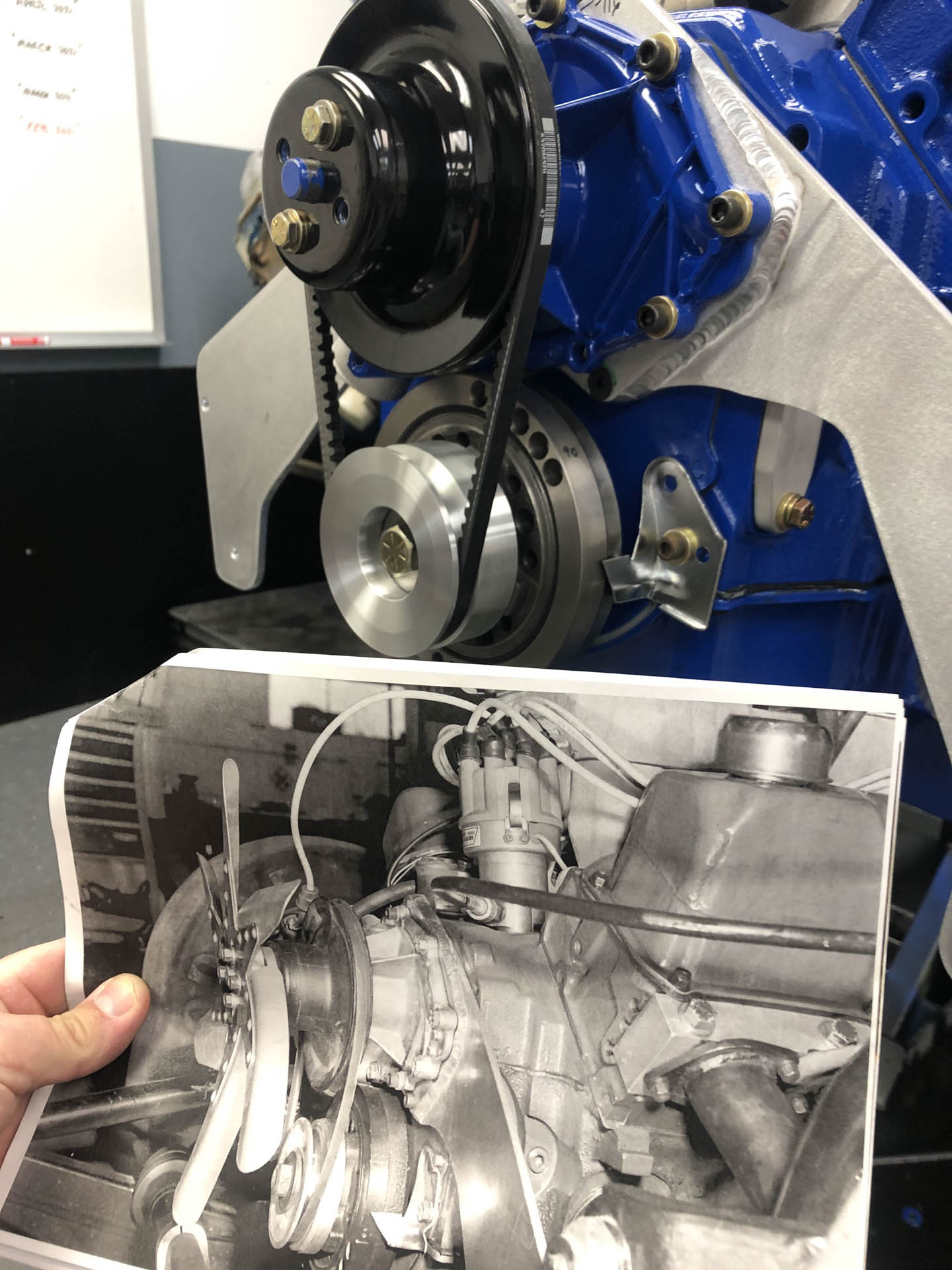

While it went off for paint, the real work began on pooling together an original drivetrain. From the crank bolt to the rear lug nuts, they wanted a period-correct machine through-and-through, which began with a massive research project through Roush’s archives to find reference photos. Thankfully, Roush himself had enough foresight to keep one of the original motors, plenty of spare components, and even one of the original Lenco transmissions.

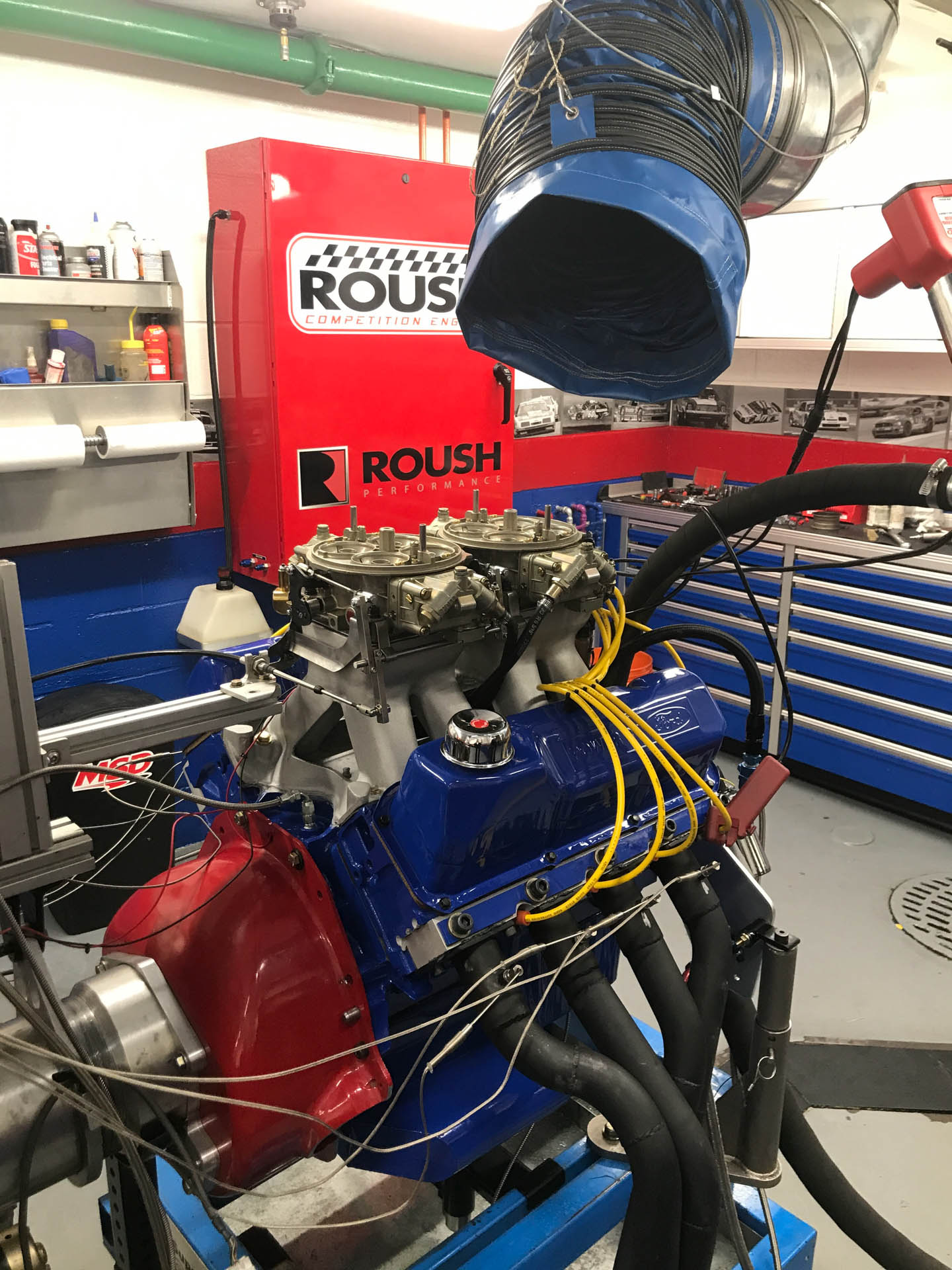

Once everything coalesced, Roush charged his Roush Competition Engines division with rebuilding the engine with only minor updates to help bulletproof it for Roush’s enjoyment. Those upgrades focused on the valvetrain such that it could survive more usage with less maintenance than in 1974. A small sacrifice, but in person, the car is simply a functional time capsule. The real deal, here and now, and hopefully forever.

“We started to recreate the four-door Maverick too, but I don't have enough runway left to do the Tijuana Taxi,” Roush admitted. “Susan will have to do that.”

Written by Phillip Thomas

Photography by the author and courtesy of ROUSH

Under a humid spring morning in March of 1974, Wayne Gapp and Jack Roush relaunched their fresh Mustang II Pro Stock machine for a weekend of match races during Gatornationals. The Mustang II only debuted six months prior, and the duo was quick to pick one up on the rumor that it was slipperier in the wind than even the venerable Pintos. Roush would pilot the new Mustang II, while Gapp drove his Pinto.

The Mustang II had come together at the Livonia compound in Michigan, where the winter weather had prevented them from getting any real full-tilt testing done. What few eighth-mile test hits they gathered at Milan were usually met with the new car “dancing” all over the cold, wintery track conditions up north, in Roush’s words.

But with the Sunshine State’s pavement radiating with warmth, Roush worked the Mustang II like anything else. He went through the burnout box, found his spot in the timing beams, sidestepped the clutch, and came off the line in the usual routine… before the cabin was rapidly and unexpectedly exposed to the outside world at more than 150 mph like a beer can peeling apart while being shot out of a cannon.

“The first qualifying run at Gainesville, I got it up to speed and the decklid was not properly attached to the roof and I set an altitude record on decklids,” Roush proclaimed. “In the traps, all of a sudden, I hear all this noise, and the cockpit fills with combustion gas. I look around and all I can see is the whole back-end is off the car. So, it destroyed the decklid—and the Mustang II is a brand-new car in 1974. I sent somebody to Jacksonville to get a white Mustang II rental car. I took the decklid off the Hertz rental car and ran its decklid on my car for the rest of the race.”

Still, a 9.02 elapsed time on the first full hit put any questions to rest about the potency of this new combo, with that first weekend in the Mustang II at Gainseville settling with Low ET of the Meet with an 8.88 before finding itself in the finals against Wally Booth (who ran 8.87), falling to his Hornet despite the strong debut.

The Gapp and Roush Mustang II never quite held the acclaim of some of Roush’s other machines, but it’s one of the only original examples to have survived the decades. It existed in tragic irony, with the NHRA blaming the shorter wheelbase of Ford’s potent Pintos for their advantage and instituting new weight breaks that effectively made the 96-inch Mustang II useless for the class before it even made its first pass (the longer Tijuana Taxi was under construction at the same time due to the rules changes).

Despite this, it remained in the back of his mind as something of a missed opportunity. Roush himself has finally settled down a little, partly after a bout with cancer and partly due to the pandemic itself idling motorsports, and he’s had time to reprioritize his efforts at home. The Mustang II left stashed in a dark corner of the shop for close to 30 years, became the target of Roush’s notoriously intense, laser-beam focus.

Back in the Day

The foundation of the Gapp and Roush Mustang II is fairly well known to diehards, but with its disappearance since those days in the mid-’70s, the car almost left the public record. It was built to replace the infamous Pinto that Roush had rolled the year prior, leaving him knocked out after crawling from the rolled-up wreckage.Like Dyno Don’s Mustang II, Don Hardy was phoned up to build the double-rail tube chassis. Little tricks here and there are simply a result of the times, despite being something of a silhouette car, you still find a smattering of factory parts throughout — notably, the upper and lower control arms, modified Corvair and Chevy II arms, specifically. Trimmed down for packaging around the chassis and headers and tied to a set of aluminum Strange Engineering uprights, the arms are supported by Monroe coilovers. A Pinto steering rack was used, and in a you’ll-never-see-this-today example of old-school problem solving, a flexible spring shaft/coupler was used to link the column to the rack-and-pinion. Not unlike those flexible spring socket extensions, but certainly unlike any solution you’ll find today. Following those frame rails towards the back, the narrowed 9-inch housing was hung by a pair of ladder bars. Schiefer 5.67 gears were wrapped around a Strange Engineering spool, with Strange axles branching from there to the Motor Wheel rear hoops shod with 14x32x15 Firestone slicks.

Unlike Dyno Don’s Mustang II, Gapp and Roush only chose to acid dip the doors, rationalizing the choice in that the weight loss would be replaced in Bondo just to get the panels straight again, and ideally, the body would last longer over time. Though they were part of the Ford factory team, they still operated their cars like an OEM program. The Mustang II lived up to those expectations wherever it could. The front sheet metal was replaced with fiberglass panels from A&A as standard practice, and throughout the chassis, new ballast mounting locations were added so that Gapp and Roush could get a real handle on weight transfer. To seal everything in, Chuck Miller painted a disco-era perfect strip package that was dominated by the Blue Oval’s official colors suspended deep under metallic flake before Paul Hatton lettered the Mustang II up.

All this was wrapped around a factory-block 351 Cleveland that kept the stock bore and stroke, but beyond that, little remained faithful to the Blue Oval’s original specs. Roush machined custom Chevy rods to fit the 351 crankshaft by BRC (increasing rod length from 5.775 inches to 6.060 inches, moving the piston wrist-pin location to accommodate), who also produced the one-off, Gapp-and-Roush-designed, set of pop-up pistons. In an era before dry sump became routine, Gapp and Roush’s team would relocate the oil pickup in the heavily-modified and baffled oil pan, running a section of hose to a fixed oil pump pickup intake down in the sump to eliminate the failure-prone factory pickup tubes. They also transformed the oil pan with a rear-sump configuration to allow the steering hardware room to swing. Trap doors, along with a widened reservoir that flared out from the sides, worked together to retain a supply of oil down low, keeping the oil galleys above fed as much as keeping windage down. Gapp and Roush utilized oil restrictors designed for Moroso to force as much volume as possible into the main bearings.

As you work your way up the combo, there’s still a wealth of tricks to off-the-shelf hardware. Notably, the heads had high-port adapter plates designed for the exhaust ports to improve their overall trajectory out of the combustion chamber. Every facet of the ports and chambers was also tweaked before a heavily chopped Edelbrock tunnel ram was set atop. It had its plenum volume reduced and excess webbing was removed to improve airflow around the runners, which were also shortened to optimize the nipped-and-tucked tunnel ram for the buzzing rpm range of Pro Stock.

The whole song-and-dance was led by a General Kinetics camshaft, which bumped a set of GK roller lifters before flipping that motion over the now obsessively tweaked top-end. The stock guide plates were modified such that each could be fitted to an individual pushrod’s geometry. GK roller rockers ride underneath a Jomar stud girdle before a set of factory rocker covers — cut and welded over another pair to double-up the height — capped all those metallic secrets.

Handling the fueling are a pair of 1050 CFM Holley Dominators, though the ignition system was a trick example of early electronic ignition, utilizing ACCEL’s BEI system which placed an optical ring on the distributor shaft, with a phototransistor that found timing via a series of gaps in the BEI’s disc — not unlike GM’s Optispark. This gave them timing control down to the quarter-of-a-degree. Naturally, towering Lenco Levers split gears behind the 351, with a Long-style lever clutch taking up the task of capturing all the rotating chaos possible from 10,000-rpm launches.

And Back to Today

How’d it feel to pull those levers again, Jack? “Oh, you can’t imagine,” he admitted with a smile that failed to stay restrained.

As Tyler Wolfe, Roush’s Historian, and I rounded the corner of the shop, there he was. Roush and one of his restoration guys were making a handful of adjustments to the linkages while the Lenco was on a bench after its initial post-restoration test. Frankly, it also just seemed like he was reliving a highlight reel he hadn’t had in the memory banks for some time — working his routine across the levers subconsciously before carefully resetting them one by one, racking each forward like a bolt-action.

This same building used to host many NASCAR Cup-car builds, a side room where Merlin V-12s are hoarded was once the engine dyno lab. While Covid had him home in Livonia more and more, and further away from the grind of chasing his Roush-Fenway-Keselowski Racing cars across the country, Roush finally decided to reclaim the space and began working on not just his projects, but restoring examples of his children’s and grandchildren’s race cars. However, it was also the purgatory for the Mustang II for many decades, practically forgotten about while Roush built his empire.

“I thought I was gonna live forever and that I could do it whenever I wanted. A couple of things happened to my health that gave me wakeup calls, so I said, ‘If I'm going to get this thing together and put it back in the same condition it had in its heyday, I need to do it now, not leave it to someone else to do later,’” Roush explained. “I had some cancer, and I had some challenges with that. I made a short list of what I wanted to do with my time and fixing that car was one of them. I don't have any more Pro Stock cars, but when my daughter Susan [Roush-McClenaghan] decided to start drag racing 10 years ago, I had a crew of two or three people who worked on restorations for me all the time. I had the engineering business doing well, and I had the road racing business and NASCAR business doing well. And so, since I worked seven days a week for the company, I wanted to do something for myself. That's when I started restoring all these Pro Stock cars. I let the company pay since I was being productive!”

After that initial outing in 1974, Roush would continue to campaign the Mustang II for the rest of the season in match races, but with the NHRA’s wheelbase rules still pulling the strings, it had lost its chance as a full-time contender in Pro Stock. The following year, 1975, Gapp and Roush dissolved their union due to irreconcilable differences in business. Jack sold the Mustang II to Luis Forteza, who imported the de-branded Pro Stocker to Puerto Rico, where he campaigned it over several years with his family. In the time since, Roush moved away from Pro Stock, entering NASCAR, Trans-Am, and international endurance racing over the following decades.

The empire sprouted, first with Roush Performance Engineering, branching off into Engine & Control Systems (which grew into Roush Industries for their non-motorsport clients), later Roush Performance Products for the DIY crowd building their hi-po Mustangs — today, a stroll down the block reveals what feels like a dozen or more buildings around Livonia where a different tangent of business is housed. Even when the opportunity arose in the ’90s to repurchase the Mustang II, it was, of course, put out of sight, far out of mind while these off-shoots grew.

With decades of neglect, the car was rough, but still fairly complete. The work was spearheaded by Andy Robinson and Steve Fackender. Every composite part in the nose had warped with age and use but was still repairable. The body came to them with less paint, but it too was in great shape, all things considered. Most of the time was just spent fixing fitment issues. In the process, every decal was scanned, cataloged, and recreated — building something of a small archive in the process too.

While it went off for paint, the real work began on pooling together an original drivetrain. From the crank bolt to the rear lug nuts, they wanted a period-correct machine through-and-through, which began with a massive research project through Roush’s archives to find reference photos. Thankfully, Roush himself had enough foresight to keep one of the original motors, plenty of spare components, and even one of the original Lenco transmissions.

Once everything coalesced, Roush charged his Roush Competition Engines division with rebuilding the engine with only minor updates to help bulletproof it for Roush’s enjoyment. Those upgrades focused on the valvetrain such that it could survive more usage with less maintenance than in 1974. A small sacrifice, but in person, the car is simply a functional time capsule. The real deal, here and now, and hopefully forever.

“We started to recreate the four-door Maverick too, but I don't have enough runway left to do the Tijuana Taxi,” Roush admitted. “Susan will have to do that.”