Jesel Equal Eight—All Out V8

Dan Jesel Developed A Unique V8 Engine From Scratch

By Evan J. Smith

Photography by the author and courtesy of Jesel

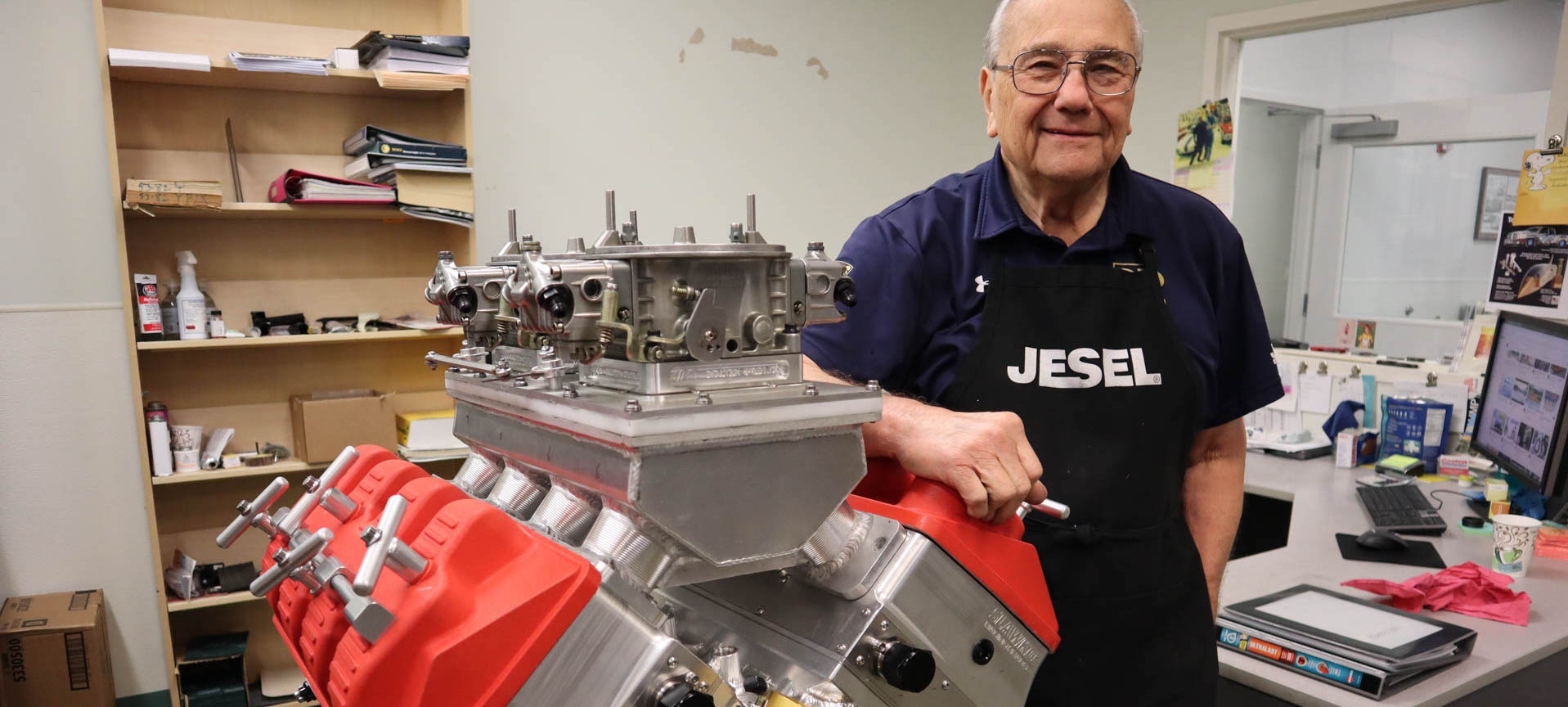

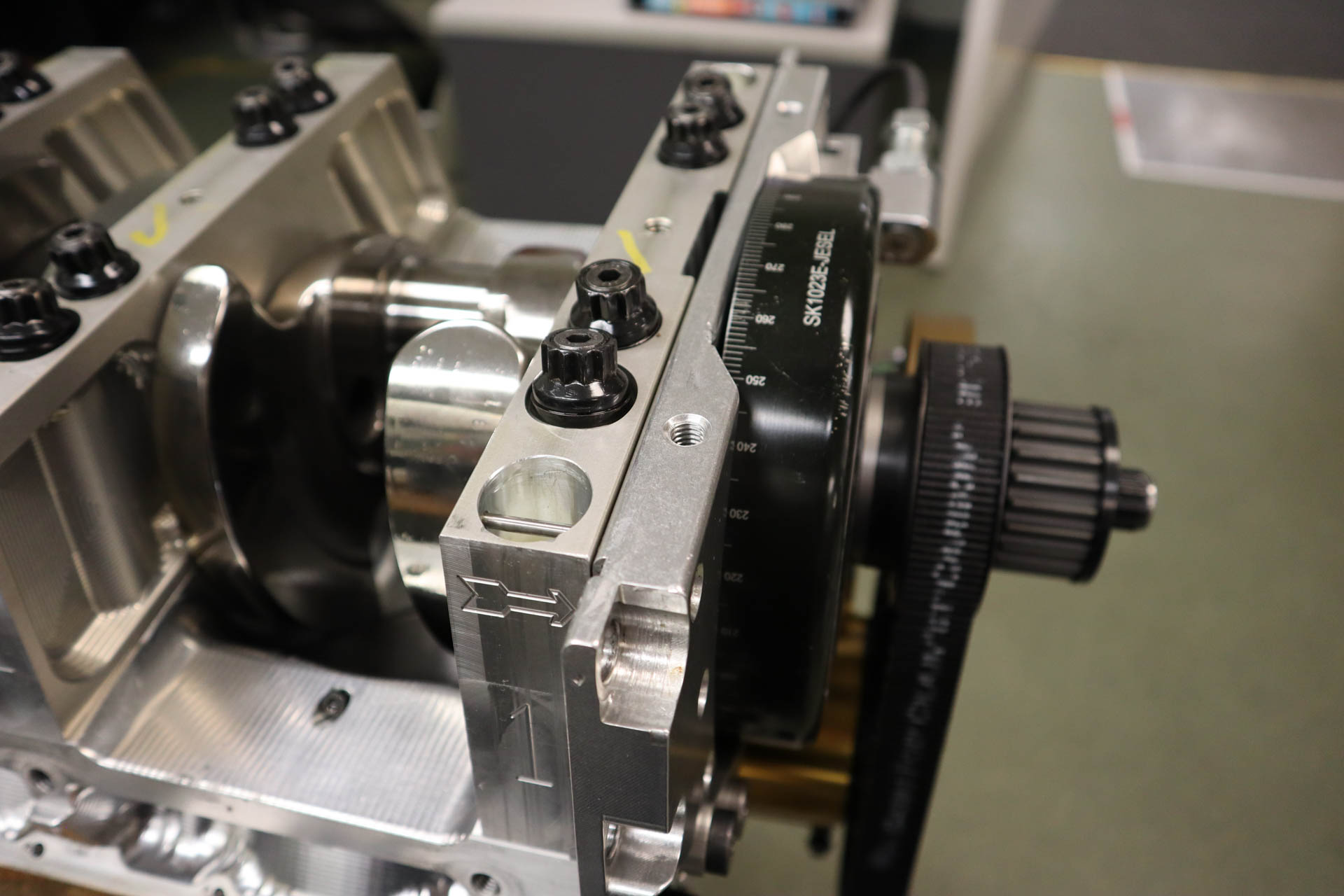

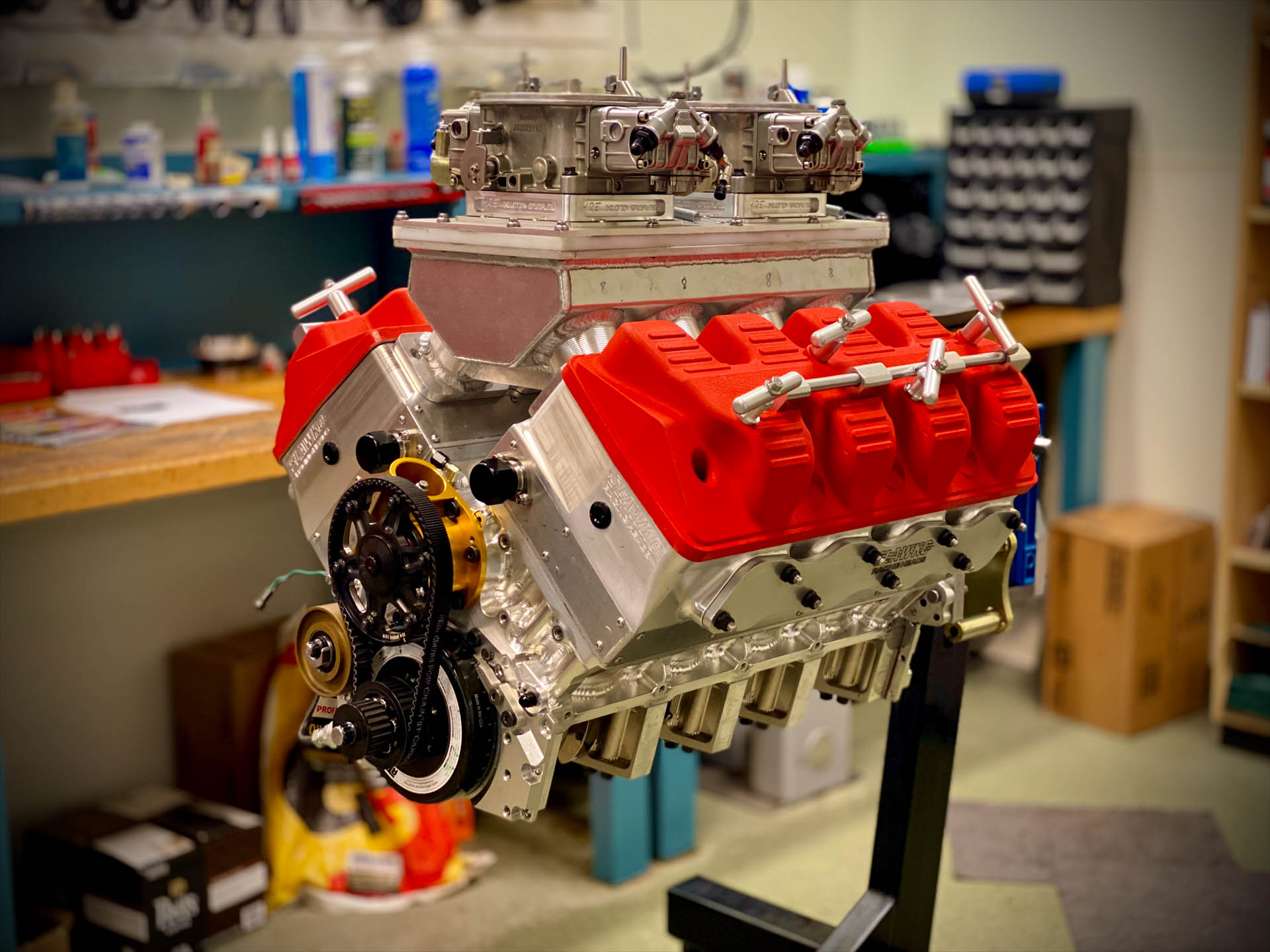

It’s likely you’ve heard the sad news about the passing of Dan Jesel, owner of Jesel Valve Train Innovation. For many decades Dan and his team created innovation that helps racers make maximum power in a reliable fashion. Rockers, lifters and belt-drives are the most common components, but over the last few years, Dan worked on a special project, one he dubbed the Equal Eight. It's a V8 engine that he designed from scratch, and with the help of some very smart individuals, it was built, tested and raced.

Dan Jesel used his decades of experience to converge on an idea that the perfect V8 would have eight equal cylinders free of compromise. If you think about it, virtually all production-based engines are subject to some form of compromise due to manufacturing cost, space limitations or emissions. Mechanically, areas that cause problems are unequal-length intake runners, non-perfect valvetrain configuration, cooling that favors certain cylinders, fuel flow, and even oiling.

Many racers think in overall power. “My engine makes 800 horsepower.” That’ a common statement, however, each of the eight cylinders is not producing exactly 100 horsepower. In fact, despite a builder or tuner’s best efforts, cylinder-to-cylinder output can vary—sometimes by a sizeable percentage.

The inequalities are due to inefficiencies in the induction system, valve timing and/or mechanical imperfections including results from windage, lifters dragging in the bore and parasitic loss, all which rob power. Some of these issues can be rectified with aftermarket blocks, heads, valve train pieces and other modifications, however, the vast majority of drag racing engines rely on factory architecture, so you’re stuck with OE port configurations, stock bore spacing, imperfect oiling, and at times, inadequate cylinder head retention.

Stock configurations were not an issue for Jesel, as the Equal Eight is just that, equal from cylinder to cylinder. Jesel initially decided on building his masterpiece as a 427-cube version to make a direct power comparison to the Chevrolet L88, 426-cube Hemi and Ford 427-, 428- and 429-displacement engines from the muscle-car era, along with the modern LS7. His target was 1,300 horsepower, or 3.1 hp per cubic inch.

The Equal Eight ran for the first time in Larry Morgan’s B/Altered Comp entry at the 2021 NHRA U.S. Nationals in Indy. Morgan ran 7.13 at 194 mph with the 441-cube Equal 8 engine, which only saw a few pulls on the dyno previously. Output was just under 1,300 horsepower at 10,000-plus rpm!

“My motivation for this project stemmed from the fact that I was tired of looking at all the compromised engines,” said Jesel, who was 80 at the time of this interview. “In so many cases, you’re trying to take a passenger car engine that’s built for the road and turn it into a race motor. Every time you wanted to improve it, you either needed a bigger bore or bigger valves and you’d just run into road blocks,” he explained. “You’re stuck with stock head bolt placement, the location of the cam and cam bearings that’s not optimum, small bore centers, odd port shapes and poor valvetrain geometry,” he explained. “The toughest thing was for me to make up my mind to actually build it instead of just looking at doing it,” he said.

But before cutting the first piece of aluminum, Jesel had to lock into design characteristics (which changed as his ideas evolved). “The first five years I went with a dry [sleeve] motor then I decided to do the wet motor, which changed the bore centers and the width of the cylinder heads. I mean when you make one change, everything else changes,” Jesel added.

In addition to making all eight cylinders equal, he also designed the engine to be easily serviced. Even the valve covers can be removed in seconds with no tools needed.

Additional features include a raised cam with optimized lobe placement, improved valvetrain geometry, the all-important equal intake and exhaust ports and additional fasteners for the cylinder heads. Jesel also optimized the lifter design (including angles), valve sizes (and angles) and even the oiling and cooling was given much thought for optimization.

“I started this 10 years ago when I turned 70,” Jesel told us, “I can’t say I spent 10 years on it, though. I’d think about it, go on to another thing and come back to it. And I’d start looking at areas like the cooling and the oil system. And then finally, we started cutting the block and heads and that was a two-to-three-year project by itself.”

The Block

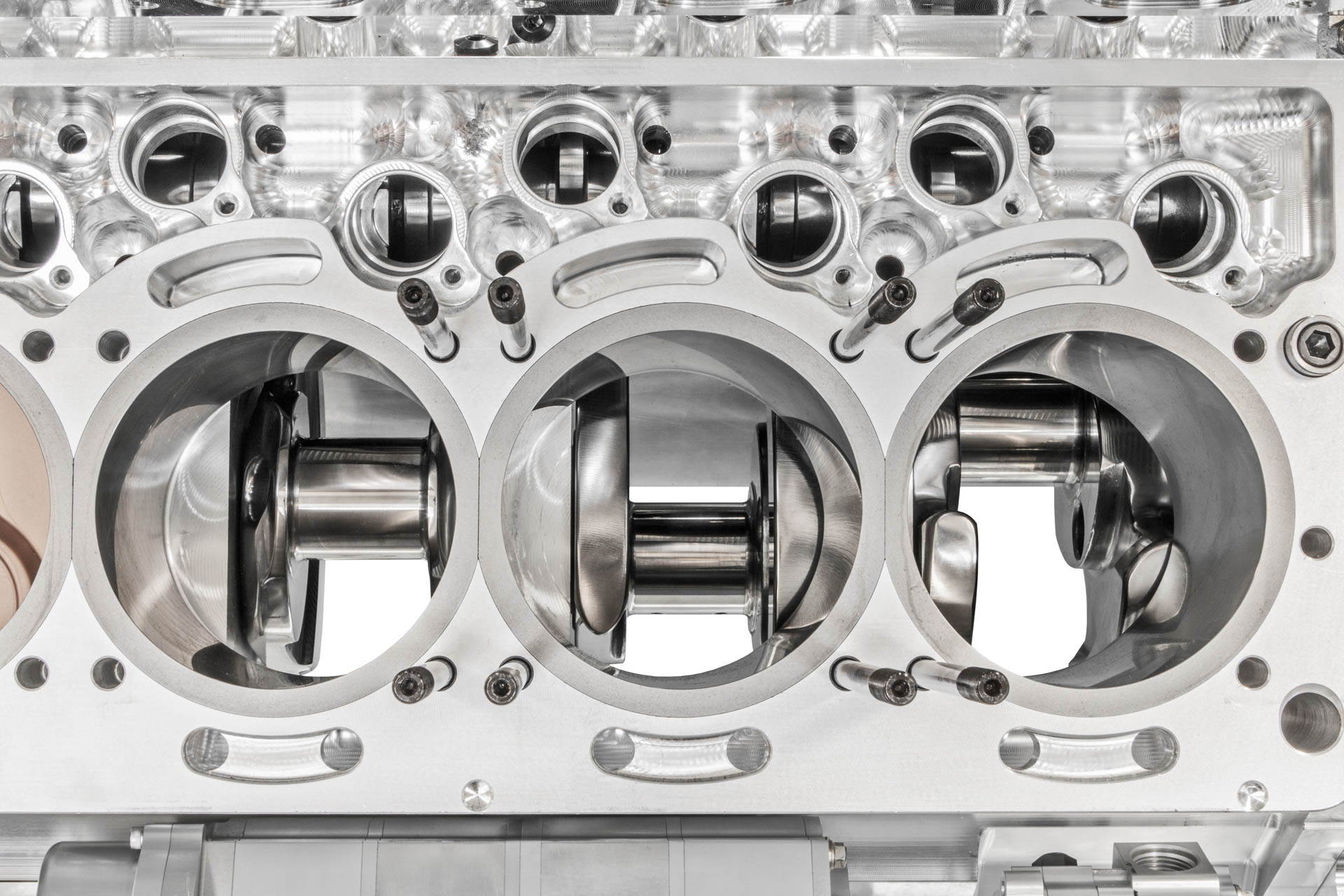

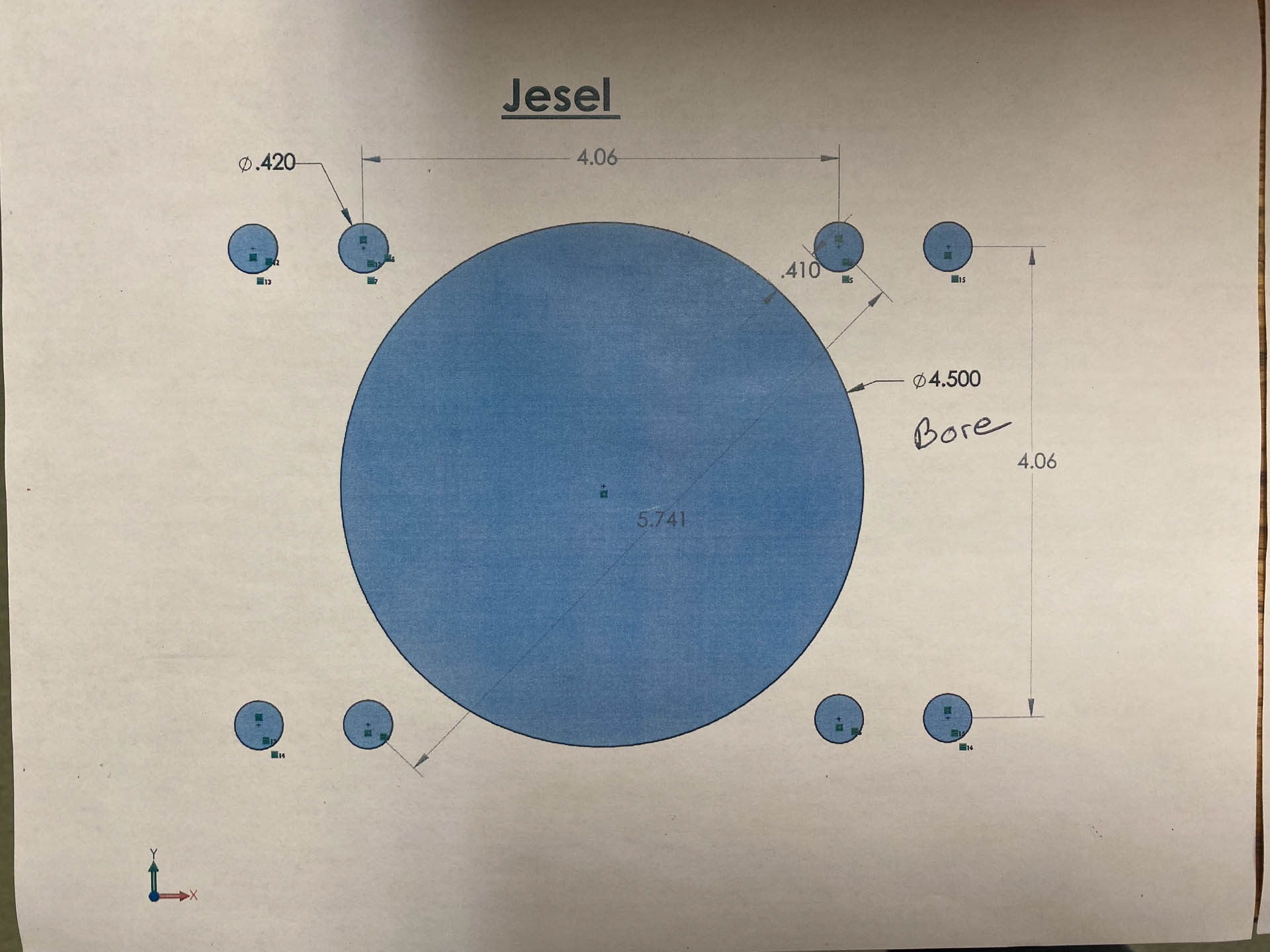

The foundation of the Equal 8 is the 90-degree billet short-deck block that was the brainchild of Jesel and famed block man Charlie Weston of Weston Machine in New Jersey. It uses wet sleeves that fit neatly in the aluminum block. And with 5.00-inch bore spacing you can go big on bore to accommodate large cubes and big valves. For example, a typical 440-450-cube engine would be limited to a 4.200-inch bore and the displacement would come from additional stroke. Bore and stroke on the Equal 8 comes in at 4.500 x 3.470-inches.

A Winberg crank was designed with wide counterweights and there’s no heavy metal used for balancing. It uses a Ford FR9 (NASCAR-style) snout and a LS9 rear bolt pattern with a one-piece seal from a BMW because the parts work well and are common. The counterweight design also means a reduction in inertia and losses due to windage.

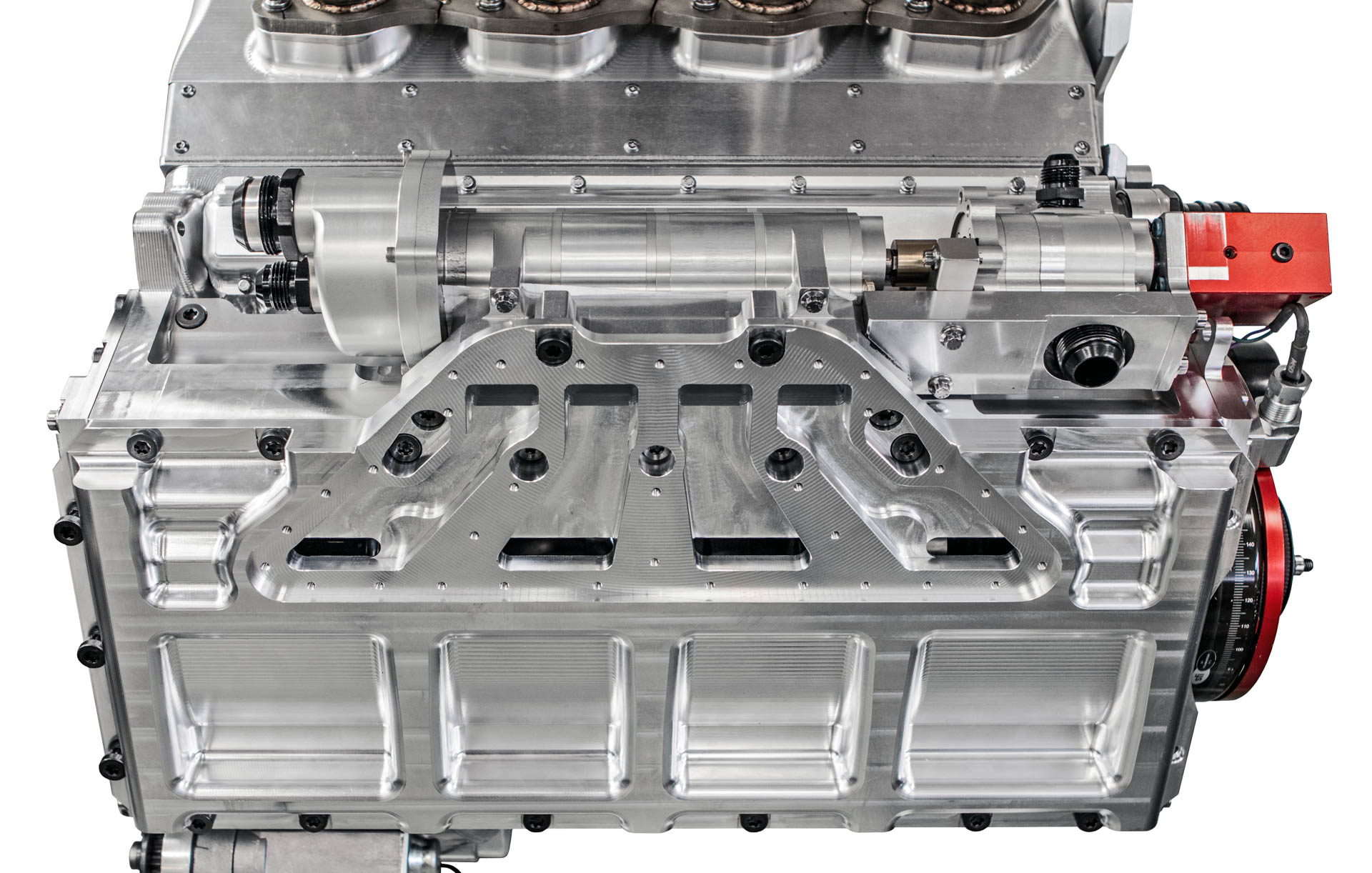

The crank is retained by five main caps, which also serve as patricians between the cylinders. Separating the cylinders in the crankcase helps control windage and reduces pumping losses. Essentially, the Equal 8 acts like 4 individual V2 engines. Furthermore, each pair of cylinders has its own dry-sump stage, and the pump is integrated into the block and the billet pan. Great attention was paid to oil drain back to prevent oil from falling on the crankshaft. Jesel also incorporated an additional scavenging pump driven off the back of the cam that evacuates oil from the lifter valley to prevent oil from draining directly onto the crank.

Valve Action

Even the best OE valve trains have shortcomings, so Jesel improved valve action by aligning the pushrods using staggered lifter bores. This allows the 1-inch diameter lifters to push straight up for perfect alignment on the rockers. This keeps the valvetrain geometry in check and prevents losses due to obscure angularity. You’ll also note the camshaft is located higher than normal in the block. This allows for shortened push rods for strength and weight reduction.

Crank-to-cam centers measure 6.300-inch, as compared to 4.520-inches and 5.150-inches on Chevrolet Small- and Big-Block engines respectively. And please note the cavernous cam tunnel that’s 3.500-inches in diameter.

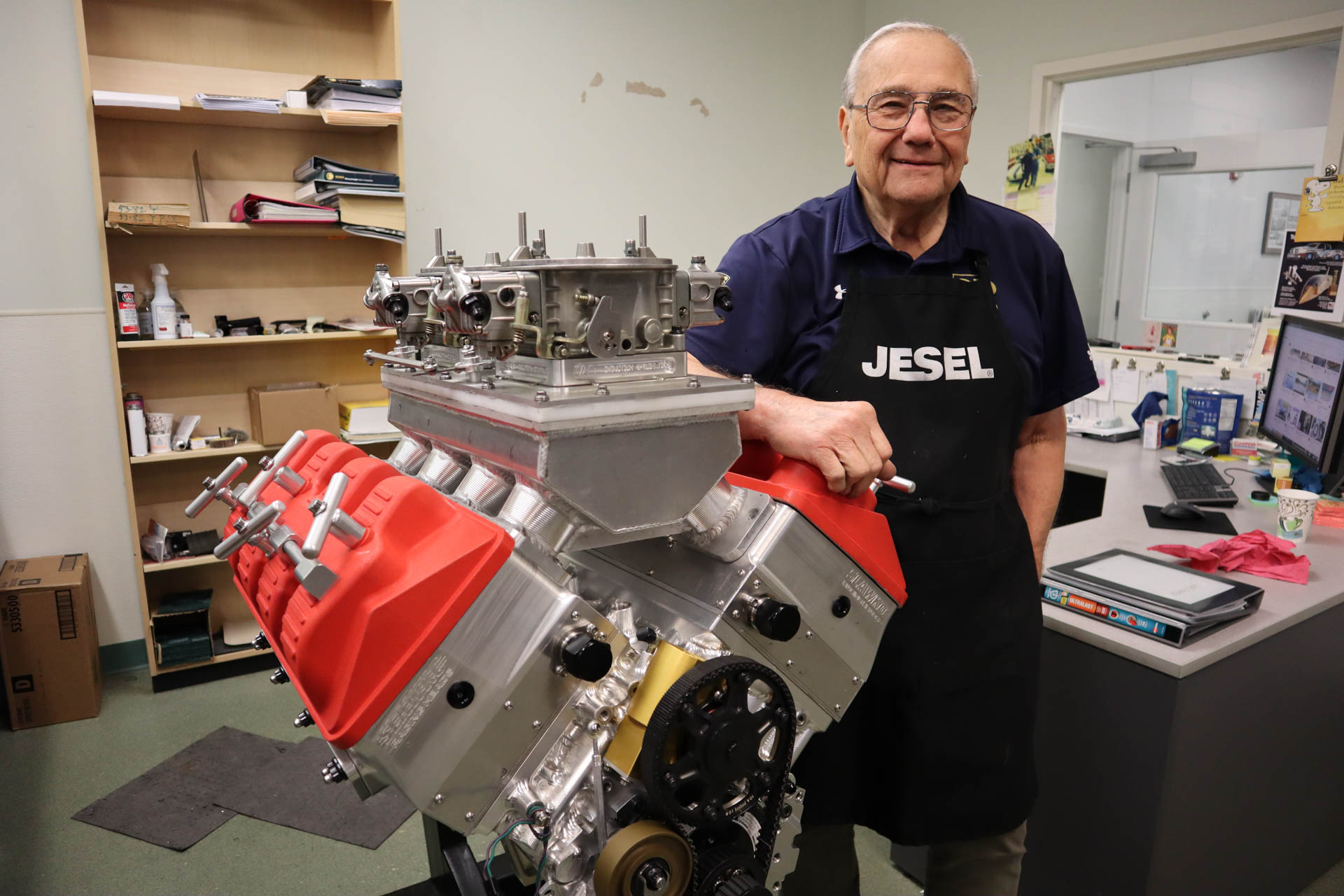

In typical V8 engines the cam bearings are aligned with the main bearings, with the cam lobes fitted in between the journals. This is not optimum for valve train geometry, so Jesel set the cam lobes in perfect alignment and then he located the bearing journals and used clamshell bearings to make it work. As you’d expect, the cam is Tool Steel, has over 1.100-inch lift and the narrow 5/16-inch lobes allow for proper lifter clearance.

Big Heads-Big Flow

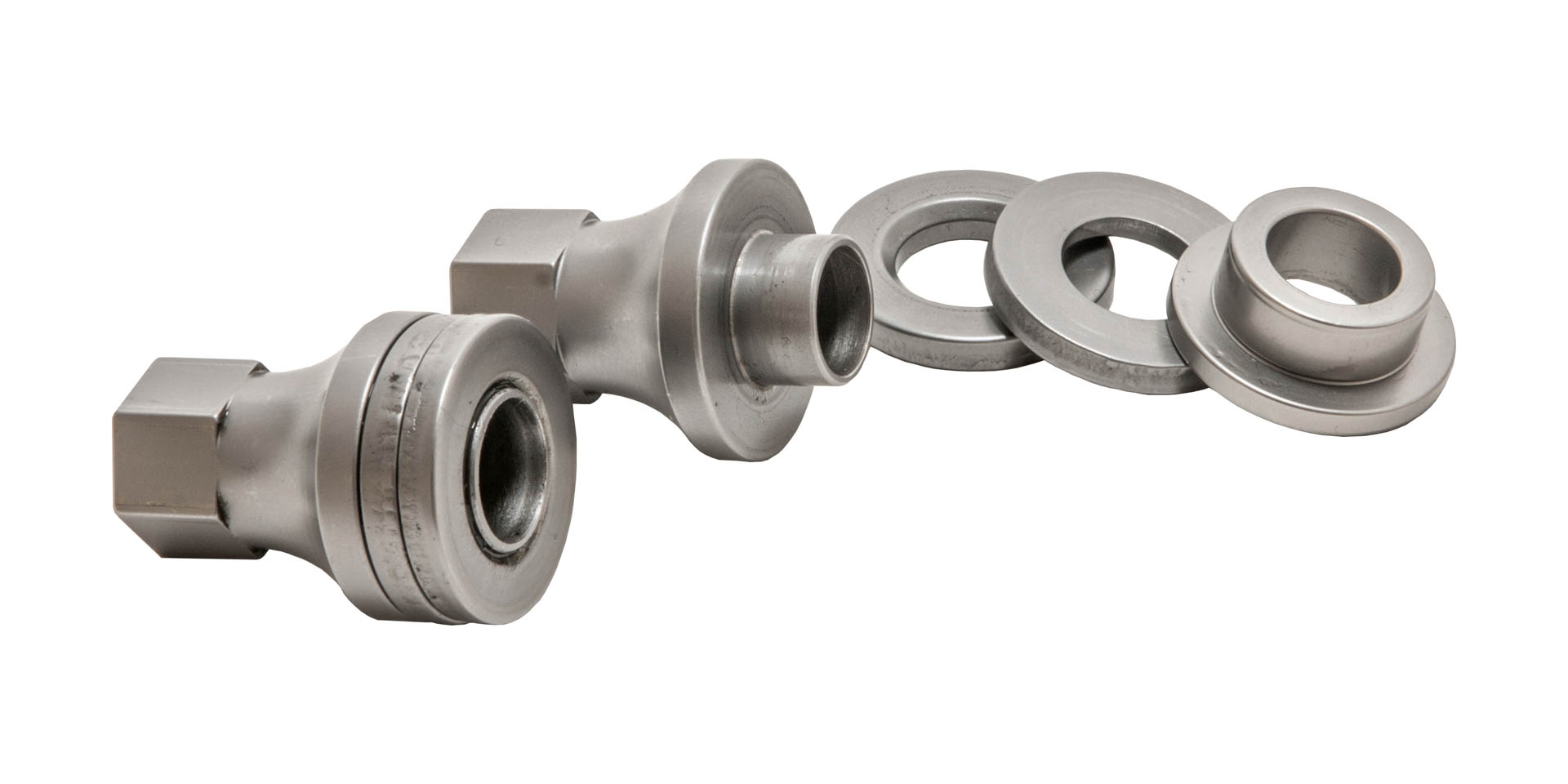

Renowned cylinder head guru Tom Slawko of Slawko Racing Heads helped design the heads that have many unique features. These include optimized port and combustion chamber design, spark plug placement, cooling passages and valve angles. Other notables are beryllium copper valve spring seats that feature adjustability for height (no shims needed), and the cylinder head retaining studs, of which there are four per bore (16 per bank). They even use special washers on the fasteners for more accurate fastening. Jesel Pro Steel rockers open the valves and use needle roller tips and Tool Steel ball-end lash adjusters.

Lube Is Important, Too!

Lubrication is key to performance and survival, so Dan Jesel carefully planned the system. A gear-driven pump supplies the oil under pressure, with the main bearings being prioritized. Oil drain back was also important, and so he designed it to route through passages on the return to keep the oil from draining onto the crank. Jesel put a lot of effort into reducing windage and evacuating crankcase pressure. He designed the main caps for strength and to also serve as walls or partitions to separate each pair of cylinders. This creates four separate sections, which are scavenged with a four-stage Daily Dry Sump Pump.

Stay Cool

Jesel understood the importance of cooling, as temperatures must be equalized from cylinder to cylinder to make equal power. If a cylinder is hotter than the rest, it won’t tolerate as much timing and this will hurt power. So, he used billet aluminum cooling manifolds that attach to the block and feed water to the exhaust side of the head first, before moving through the rest of the head and the block. In all, the Equal 8 is a well-though-out internal combustion engine that’s racer friendly and makes great power.

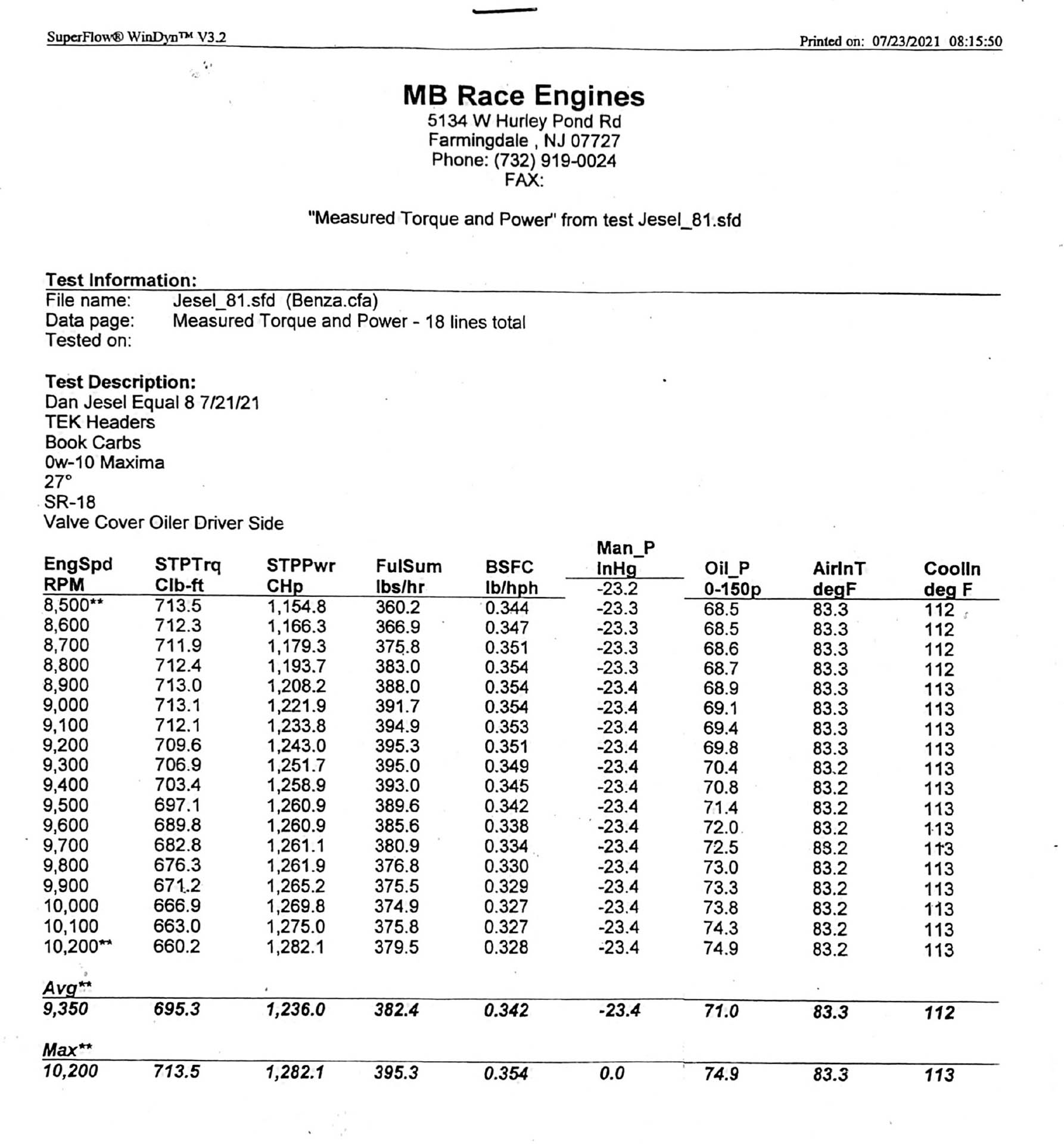

What’s most impressive is the Equal 8 made 1,282.1 horsepower at 10,200 rpm and you’ll note it was still climbing when they cut the pull. This was during the first dyno session, with very little run time. Jesel commented that peak power was likely to be higher, but the point was proven and it was time to get the engine off the dyno and into Larry Morgan’s car for real-world testing.

“After spending that much time, it was rewarding to hear it run,” said Dan Jesel, “And we really got to that point fairly quick. Now when it goes back on [the dyno] we have a different cam and collectors and that’s about it,” he said. “I’m not going to do much more, I’ll just do the other motors. It should be in the hands of racers and engine builders. I mean, I’m not claiming I’m an engine builder. I designed the block and the configuration. I just figured engines this big don’t get close to 10,000, but we went to 10,400 and it didn’t fall off, and that’s pretty exciting.”

Equal 8 Engine Specifications

Block: Aluminum 90-degree V8 Wet Sleeve

Bore: 4.500-inches

Stroke: 3.470-inches

Displacement: 441 cubic inches

Deck Height: 8.50-inches

Cam Journals: 1.687-inches

Main Journals: 2.560-inches

Crankshaft: Winberg Billet Steel

Connecting rods: Steel

Rod Journals: 1.850-inches

Camshaft: Lift 1.100-inch; Exhaust 1.0-inch/Duration 289-degrees intake; 304-degrees exhaust

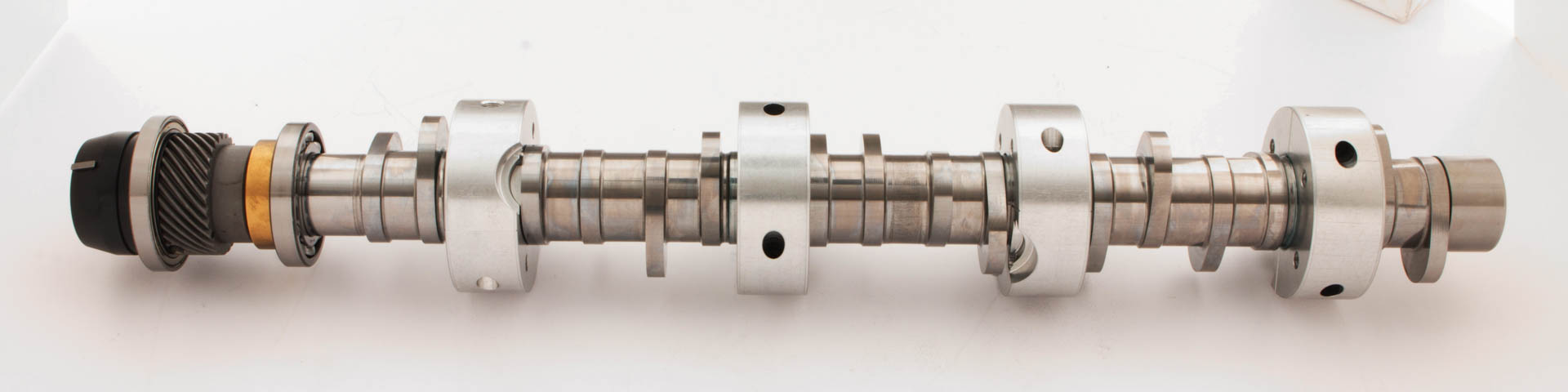

Cam Drive: External Jesel Belt Drive

Cylinder Heads: Slawko Racing Billet Aluminum

Valves: Intake 2.400-inches, 9-degree angle with 3-degree cant; Exhaust 1.720-inches -2-degree angle, 1.5-degree cant

Rockers: Jesel Pro Steel, Intake 1.95:1 Exhaust 1.90:1

Compression Ratio: 16:1

Pushrods: Intake 7.5-inches Exhaust 8.7-inches

Horsepower: 1,285 at 12,200 rpm

Torque: 713 @ 8,500 rpm

Redline: 12,500 rpm

Dan Jesel Developed A Unique V8 Engine From Scratch

By Evan J. Smith

Photography by the author and courtesy of Jesel

It’s likely you’ve heard the sad news about the passing of Dan Jesel, owner of Jesel Valve Train Innovation. For many decades Dan and his team created innovation that helps racers make maximum power in a reliable fashion. Rockers, lifters and belt-drives are the most common components, but over the last few years, Dan worked on a special project, one he dubbed the Equal Eight. It's a V8 engine that he designed from scratch, and with the help of some very smart individuals, it was built, tested and raced.

Dan Jesel used his decades of experience to converge on an idea that the perfect V8 would have eight equal cylinders free of compromise. If you think about it, virtually all production-based engines are subject to some form of compromise due to manufacturing cost, space limitations or emissions. Mechanically, areas that cause problems are unequal-length intake runners, non-perfect valvetrain configuration, cooling that favors certain cylinders, fuel flow, and even oiling.

Many racers think in overall power. “My engine makes 800 horsepower.” That’ a common statement, however, each of the eight cylinders is not producing exactly 100 horsepower. In fact, despite a builder or tuner’s best efforts, cylinder-to-cylinder output can vary—sometimes by a sizeable percentage.

The inequalities are due to inefficiencies in the induction system, valve timing and/or mechanical imperfections including results from windage, lifters dragging in the bore and parasitic loss, all which rob power. Some of these issues can be rectified with aftermarket blocks, heads, valve train pieces and other modifications, however, the vast majority of drag racing engines rely on factory architecture, so you’re stuck with OE port configurations, stock bore spacing, imperfect oiling, and at times, inadequate cylinder head retention.

Stock configurations were not an issue for Jesel, as the Equal Eight is just that, equal from cylinder to cylinder. Jesel initially decided on building his masterpiece as a 427-cube version to make a direct power comparison to the Chevrolet L88, 426-cube Hemi and Ford 427-, 428- and 429-displacement engines from the muscle-car era, along with the modern LS7. His target was 1,300 horsepower, or 3.1 hp per cubic inch.

The Equal Eight ran for the first time in Larry Morgan’s B/Altered Comp entry at the 2021 NHRA U.S. Nationals in Indy. Morgan ran 7.13 at 194 mph with the 441-cube Equal 8 engine, which only saw a few pulls on the dyno previously. Output was just under 1,300 horsepower at 10,000-plus rpm!

“My motivation for this project stemmed from the fact that I was tired of looking at all the compromised engines,” said Jesel, who was 80 at the time of this interview. “In so many cases, you’re trying to take a passenger car engine that’s built for the road and turn it into a race motor. Every time you wanted to improve it, you either needed a bigger bore or bigger valves and you’d just run into road blocks,” he explained. “You’re stuck with stock head bolt placement, the location of the cam and cam bearings that’s not optimum, small bore centers, odd port shapes and poor valvetrain geometry,” he explained. “The toughest thing was for me to make up my mind to actually build it instead of just looking at doing it,” he said.

But before cutting the first piece of aluminum, Jesel had to lock into design characteristics (which changed as his ideas evolved). “The first five years I went with a dry [sleeve] motor then I decided to do the wet motor, which changed the bore centers and the width of the cylinder heads. I mean when you make one change, everything else changes,” Jesel added.

In addition to making all eight cylinders equal, he also designed the engine to be easily serviced. Even the valve covers can be removed in seconds with no tools needed.

Additional features include a raised cam with optimized lobe placement, improved valvetrain geometry, the all-important equal intake and exhaust ports and additional fasteners for the cylinder heads. Jesel also optimized the lifter design (including angles), valve sizes (and angles) and even the oiling and cooling was given much thought for optimization.

“I started this 10 years ago when I turned 70,” Jesel told us, “I can’t say I spent 10 years on it, though. I’d think about it, go on to another thing and come back to it. And I’d start looking at areas like the cooling and the oil system. And then finally, we started cutting the block and heads and that was a two-to-three-year project by itself.”

The Block

The foundation of the Equal 8 is the 90-degree billet short-deck block that was the brainchild of Jesel and famed block man Charlie Weston of Weston Machine in New Jersey. It uses wet sleeves that fit neatly in the aluminum block. And with 5.00-inch bore spacing you can go big on bore to accommodate large cubes and big valves. For example, a typical 440-450-cube engine would be limited to a 4.200-inch bore and the displacement would come from additional stroke. Bore and stroke on the Equal 8 comes in at 4.500 x 3.470-inches.

A Winberg crank was designed with wide counterweights and there’s no heavy metal used for balancing. It uses a Ford FR9 (NASCAR-style) snout and a LS9 rear bolt pattern with a one-piece seal from a BMW because the parts work well and are common. The counterweight design also means a reduction in inertia and losses due to windage.

The crank is retained by five main caps, which also serve as patricians between the cylinders. Separating the cylinders in the crankcase helps control windage and reduces pumping losses. Essentially, the Equal 8 acts like 4 individual V2 engines. Furthermore, each pair of cylinders has its own dry-sump stage, and the pump is integrated into the block and the billet pan. Great attention was paid to oil drain back to prevent oil from falling on the crankshaft. Jesel also incorporated an additional scavenging pump driven off the back of the cam that evacuates oil from the lifter valley to prevent oil from draining directly onto the crank.

Valve Action

Even the best OE valve trains have shortcomings, so Jesel improved valve action by aligning the pushrods using staggered lifter bores. This allows the 1-inch diameter lifters to push straight up for perfect alignment on the rockers. This keeps the valvetrain geometry in check and prevents losses due to obscure angularity. You’ll also note the camshaft is located higher than normal in the block. This allows for shortened push rods for strength and weight reduction.

Crank-to-cam centers measure 6.300-inch, as compared to 4.520-inches and 5.150-inches on Chevrolet Small- and Big-Block engines respectively. And please note the cavernous cam tunnel that’s 3.500-inches in diameter.

In typical V8 engines the cam bearings are aligned with the main bearings, with the cam lobes fitted in between the journals. This is not optimum for valve train geometry, so Jesel set the cam lobes in perfect alignment and then he located the bearing journals and used clamshell bearings to make it work. As you’d expect, the cam is Tool Steel, has over 1.100-inch lift and the narrow 5/16-inch lobes allow for proper lifter clearance.

Big Heads-Big Flow

Renowned cylinder head guru Tom Slawko of Slawko Racing Heads helped design the heads that have many unique features. These include optimized port and combustion chamber design, spark plug placement, cooling passages and valve angles. Other notables are beryllium copper valve spring seats that feature adjustability for height (no shims needed), and the cylinder head retaining studs, of which there are four per bore (16 per bank). They even use special washers on the fasteners for more accurate fastening. Jesel Pro Steel rockers open the valves and use needle roller tips and Tool Steel ball-end lash adjusters.

Lube Is Important, Too!

Lubrication is key to performance and survival, so Dan Jesel carefully planned the system. A gear-driven pump supplies the oil under pressure, with the main bearings being prioritized. Oil drain back was also important, and so he designed it to route through passages on the return to keep the oil from draining onto the crank. Jesel put a lot of effort into reducing windage and evacuating crankcase pressure. He designed the main caps for strength and to also serve as walls or partitions to separate each pair of cylinders. This creates four separate sections, which are scavenged with a four-stage Daily Dry Sump Pump.

Stay Cool

Jesel understood the importance of cooling, as temperatures must be equalized from cylinder to cylinder to make equal power. If a cylinder is hotter than the rest, it won’t tolerate as much timing and this will hurt power. So, he used billet aluminum cooling manifolds that attach to the block and feed water to the exhaust side of the head first, before moving through the rest of the head and the block. In all, the Equal 8 is a well-though-out internal combustion engine that’s racer friendly and makes great power.

What’s most impressive is the Equal 8 made 1,282.1 horsepower at 10,200 rpm and you’ll note it was still climbing when they cut the pull. This was during the first dyno session, with very little run time. Jesel commented that peak power was likely to be higher, but the point was proven and it was time to get the engine off the dyno and into Larry Morgan’s car for real-world testing.

“After spending that much time, it was rewarding to hear it run,” said Dan Jesel, “And we really got to that point fairly quick. Now when it goes back on [the dyno] we have a different cam and collectors and that’s about it,” he said. “I’m not going to do much more, I’ll just do the other motors. It should be in the hands of racers and engine builders. I mean, I’m not claiming I’m an engine builder. I designed the block and the configuration. I just figured engines this big don’t get close to 10,000, but we went to 10,400 and it didn’t fall off, and that’s pretty exciting.”

Equal 8 Engine Specifications

Block: Aluminum 90-degree V8 Wet Sleeve

Bore: 4.500-inches

Stroke: 3.470-inches

Displacement: 441 cubic inches

Deck Height: 8.50-inches

Cam Journals: 1.687-inches

Main Journals: 2.560-inches

Crankshaft: Winberg Billet Steel

Connecting rods: Steel

Rod Journals: 1.850-inches

Camshaft: Lift 1.100-inch; Exhaust 1.0-inch/Duration 289-degrees intake; 304-degrees exhaust

Cam Drive: External Jesel Belt Drive

Cylinder Heads: Slawko Racing Billet Aluminum

Valves: Intake 2.400-inches, 9-degree angle with 3-degree cant; Exhaust 1.720-inches -2-degree angle, 1.5-degree cant

Rockers: Jesel Pro Steel, Intake 1.95:1 Exhaust 1.90:1

Compression Ratio: 16:1

Pushrods: Intake 7.5-inches Exhaust 8.7-inches

Horsepower: 1,285 at 12,200 rpm

Torque: 713 @ 8,500 rpm

Redline: 12,500 rpm